Note: This is the fourth part of a series of blog posts examining the impact of changes to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) on New York City’s coastal neighborhoods, which are home to many low-to-middle income homeowners. In this post, guest blogger Rebecca Elliott, a PhD candidate at UC Berkeley and the Flood Insurance Expert at Zone A New York, explains various mitigation options.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which is administered by FEMA, regulates flood insurance premiums for policyholders. In general, insurance premiums are meant to capture the risk facing a piece of property: the higher the risk, the higher the premiums. In theory, then, if you take steps to lower the risk facing your property—called “mitigation”—you should qualify for lower insurance premiums. When you mitigate, for example by elevating your home above the Base Flood Elevation (discussed in previous posts), moving your heating and cooling systems to higher floors, or retrofitting with waterproof building materials, you are changing the features of your home so that they better protect lives and property. This means you are less likely to suffer costly damages in the event of a future flood, and you reduce your insurer’s exposure to loss.

However, for the purposes of flood insurance offered through the NFIP, right now, elevation is the only mitigation option that substantially lowers flood insurance premiums for residences. This may change in the future, as policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels are currently debating whether and how to incorporate a fuller range of mitigation options into flood insurance rating (ultimately, it’s up to the NFIP). But these types of changes are by no means guaranteed and, should they succeed, they would likely be implemented more slowly than communities rebuilding would wish for. For most homeowners thinking about how to spend money on rebuilding now, elevation should likely be the top priority. For homeowners in V zones, elevation to code means having the lowest horizontal structure of the home at or above the BFE (imagine a home on stilts—the floor that sits on the stilts has to be at or above the BFE). Homeowners in A zones have other options, like abandoning lower livable floors and using them instead only for parking, building access, and/or storage, as discussed in an earlier post. For some homeowners, elevating service equipment (HVAC, hot water heaters, electrical panels, washer/dryer units, etc.) to higher floors or on outdoor platforms can also reduce flood insurance premiums (check with your insurance agent regarding eligibility).

Acknowledging that elevation is the only mitigation measure that has any significant impact on the price of premiums, this post explores other mitigation options, which may be economical insofar as they will likely reduce future flood losses, even if they won’t reduce annual premiums. If elevating is not financially or technically feasible, mitigating in other ways against flood loss will at least mean less money spent to repair and rebuild next time around. As anyone who dealt with flood insurance claims from Sandy can attest, any reduction in the physical, financial, and emotional strains of dealing with flood damages is surely a good thing. Below, we’ll briefly describe the two main types of mitigation that might be useful for New Yorkers: dry floodproofing, and wet floodproofing. For further detail, visit FEMA’s Homeowner’s Guide to Retrofitting, revised June 2014.

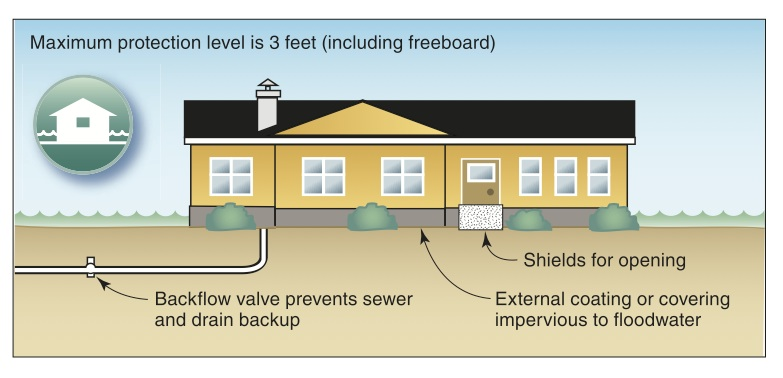

Dry floodproofing

Dry floodproofing includes actions that seal your home to prevent floodwaters from entering (See Figure 1 below). This reduces the probability that your home’s interior will be inundated, but is really only suitable for areas where flood depths are low (typically no more than two to three feet). Dry floodproofing is not appropriate in areas with a risk of high-velocity flood flow or wave action (namely V zones). You can make your home watertight by sealing the walls with waterproof coatings, impermeable membranes, or additional layers of masonry or concrete. Doors, windows, and other openings below the base flood elevation must also be equipped with permanent or removable shields, and backflow valves must be installed in sewer lines and drains.

Figure 1. A dry floodproofed home. SOURCE: FEMA Homeowner’s Guide to Retrofitting, June 2014

It is important to consult a licensed engineering or design professional when dry floodproofing, as making your house watertight can actually increase pressure on the submerged parts of the home during a flood, leading to collapsing walls, buckling floors, or even floating houses! A professional should take into consideration how walls are constructed before embarking on any plans to dry floodproof, and, in general, dry floodproofing is not recommended for homes with basements. Also keep in mind that dry floodproofing requires human action in advance of a flood event: you have to be physically capable of installing those flood shields, and you have to be able to get home to do so before the floodwaters arrive.

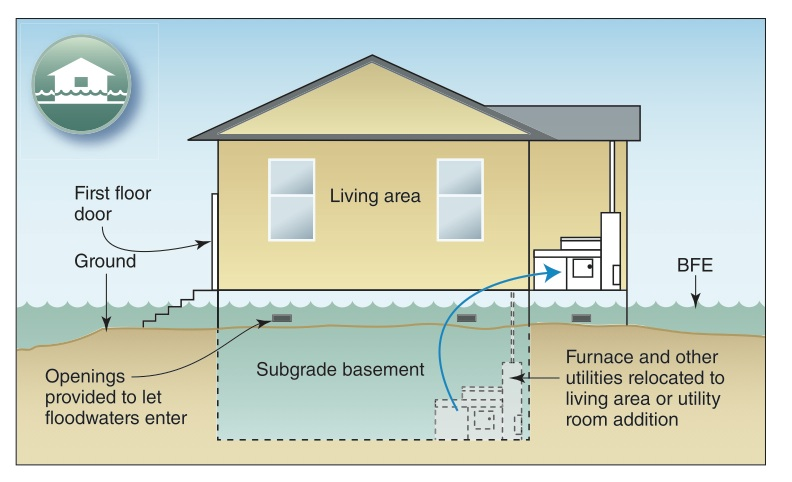

Wet floodproofing

Wet floodproofing includes actions that make portions of your home resistant to flood damage and allow water to enter during flooding; this is what makes it “wet” (See Figure 2 below). The purpose of allowing water to enter portions of the home is to deal with the pressure issue discussed above: letting the water in keeps pressure on the inside and outside of the walls equal. Because you’re letting water in, wet floodproofing is only suitable for the portions of the home that are not used for living space, for example an unfinished basement or a crawlspace. Only flood-damage-resistant building materials can be used below the flood level (e.g. clay or ceramic tiling as opposed to wood or carpet flooring, or latex paint as opposed to wallpaper, etc.).

Figure 2. A wet floodproofed home. SOURCE: FEMA Homeowner’s Guide to Retrofitting, June 2014

Wet floodproofing techniques include raising utilities and important contents (e.g. HVAC, hot water heaters, large appliances, etc.) to or above the BFE, installing and configuring electrical and mechanical systems to minimize disruptions and facilitate repairs, installing flood openings or other methods to equalize the pressure exerted by floodwaters, and installing pumps to gradually remove floodwater from basement areas after the flood. If you elevate your home, you’ll also likely use some of these wet floodproofing techniques for the portion of your home below the BFE. These techniques tend to cost less than other mitigation measures, but also keep in mind that after a flood, you’ll have a home that is wet on the inside—meaning you’ll likely see costs related to cleaning up mold, sewage, and anything else brought into your home by the floodwaters. Again, a licensed engineer or design professional should examine the construction of your home to determine if wet floodproofing is practical. Wet floodproofing will not protect your home from high-velocity flood flow and wave action, and you will need to be present to evacuate contents from the flood-prone area in advance of the flood.

Every home is different

Deciding which mitigation measures to take is ultimately a personal decision, which should take into consideration how the home is constructed, which options are technically and financially feasible, and the particular kinds of flood risks the home faces. These decisions are best made in consultation with design and engineering professionals. Before you begin any flood mitigation project, be sure that your plans are in compliance with local floodplain management ordinances and building codes, as well as any other zoning requirements.