Note: This is the third part of a series of blog posts examining the impact of changes to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) on New York City’s coastal neighborhoods, which are home to many low-to-middle income homeowners. In this post, we discuss the need for elevation financing options for homeowners in high-risk areas of the flood plain.

As we discussed in previous posts in this series, National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) rate increases will place a financial burden on low- and moderate-income homeowners, with flood insurance rates expected to rise beyond what many households can afford. Faced with these insurance changes, rising sea levels, and the damage caused by hurricanes Sandy and Irene, many New York City homeowners in flood-prone neighborhoods will need to make big decisions regarding the safety and financial sustainability of their homes in order to avoid future damage caused by extreme weather events, which will only become more severe with the effects of climate change.

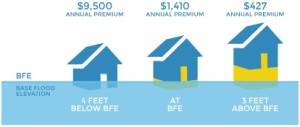

One option for homeowners to avoid the steadily rising costs of flood insurance premiums is to elevate their homes. Not only is an elevated home safer and more resistant to damage from flooding, but elevation will also result in lower flood insurance premiums. Insurance rates in high-risk flood zones are calculated by comparing the structure’s elevation from sea level as compared to its Base Flood Elevation (BFE), which is the number of feet above sea level that water is expected to rise in a 100-year flood. As seen in this graphic from New York City’s report on “A Stronger, More Resilient New York,” just a few feet of elevation can make a huge difference in lowering rates for homeowners:

Source: FEMA

Currently, elevation is the only flood mitigation option for homeowners that is recognized by the NFIP as a mitigating factor to reduce insurance premiums (though we are hopeful that the NFIP will eventually recognize other mitigation measures that are already acknowledged for other building types—but that’s for another post!). While home elevation often entails physically raising the entire house, about one half of the homes in the New York City flood plain are difficult or impossible to elevate. Some of these homes are attached to neighboring properties, while others are located on a narrow lot that cannot accommodate new stairs. For these properties, options for home elevation include extending the walls of the house upward and raising the lowest floor or converting the existing lower area of the house into a space for parking, storage, and access. In both cases, residents can elevate their homes so that the lowest floor is at or above the BFE.

Home elevation will make the structure—and the people in it—safer in times of flooding and will also result in lower insurance premiums. Thus, elevation is a great option for many homeowners. Not surprisingly, lifting a house up many feet above its current foundation is costly. Depending on structural characteristics, elevating a home can cost between $30,000 and 100,000 dollars for a typical home (and some properties will be even more expensive to elevate). The high cost makes it unlikely that most low- and moderate-income homeowners will be able to afford elevation without government or philanthropic assistance, leaving them with no options other than to pay the (unaffordable) flood premiums or sell their home.

In his affordable housing plan, Mayor Bill de Blasio calls for the exploration of a new loan program to assist low-, moderate-, and middle-income owners with resiliency upgrades. At the Center, we agree that creating such a loan program is critical to helping homeowners finance the elevation of their homes. This Resiliency Fund would incentivize banks (through an interest rate buy-down, loan loss reserve, or other guarantee mechanism) to make loans to homeowners seeking to use flood mitigation practices to protect their homes. Of course, this would be especially valuable to those banks that already hold mortgages on properties in flood-prone areas, which would have a much higher default risk without this intervention. This model is not a new one for City loan funds. HPD’s Home Improvement Program, for example, provides low-interest loans through bank partners to homeowners making critical repairs and improvements to their properties.

The Resiliency Fund is an essential component to the long-term sustainability (both in terms of the environment, and in terms of income diversity) of those neighborhoods within the flood plain. But more is needed to inform homeowners and the general public about flood insurance, generally. After two rounds of legislative reform—Biggert Waters in 2012 and the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act in 2014—understanding the current state of the flood insurance program is extremely difficult. In our next post, we will share a preview of our soon-to-be-launched flood insurance website, a resource we are creating to help homeowners and housing counselors explore and understand the complexities of these flood insurance changes and their impact on New York City homeowners.

For more information on home elevations, please see FEMA’s Guide to Elevating Your House.